|

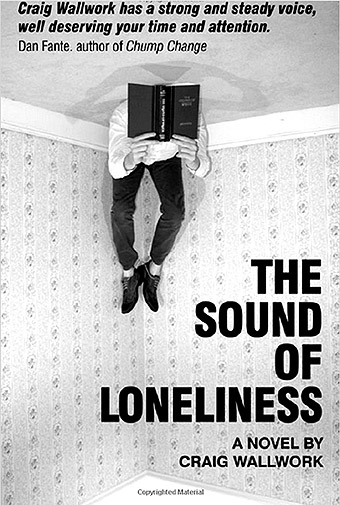

This is an unusual book in that it begins ostensibly as a comedy, full of over-the-top characters and equally extreme situations, but proceeds into deepening realism and genuine tragedy. The view of life that we are left with is profoundly pessimistic.

Written by the author of the surreal short story Gutterball’s Labyrinth that appeared in the Solid Gold anthology (of which I was Editor), The Sound of Loneliness begins with the young narrator Daniel Crabtree leaving home for the first time to live the life of the proverbial ‘tortured-soul-in-the-garret’ and write his masterpiece. Seemingly talentless but unshakable in his self-belief, he rapidly descends into a life of total penury, barely surviving the days between the arrival of each Benefit Giro Cheque, bulking out his pathetic meals of ‘soup, rolled oats, beef stock, even water’ by the addition of flour, dreading the ear-shattering early-morning attempts at song of his Irish neighbour behind the paper-thin wall. He seeks escape in absurd fantasies, and alcohol bought with money that is equally imaginary. Pausing often to philosophise, he attempts to convince himself that his situation is redeemable, success is just around the corner. One of the ways he does this is by writing optimistic letters to himself, containing the good news that he longs to hear.

This is familiar comic territory, and for quite some time what we get is not so much a developing narrative as a series of unconnected incidents in pubs, public parks and dole offices involving gross descriptions of bodily functions, the symptoms of poor diet and personal hygiene, poverty, disease and squalor. A character emerges with whom we are generally familiar, the self-important, self-pitying grand loser of modern comic fiction –Tom Sharpe’s Henry Wilt, Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole, Douglas Adams’ Ford Prefect.

This protagonist however has a facility for lyrical prose, which he exercises at unexpected moments, such as when he describes Salford as ‘a city endlessly caught on the final stroke of midnight, where a misplaced glass slipper lost in haste suggested an unseen beauty existed, but all that remained in its place were the much uglier sisters.’

The first two-thirds of the novel is genuinely witty and funny, if not particularly original, but as the story continues a number of much more serious threads emerge, including the death of an old uncle who lives alone, and the beginning of a close relationship between the twenty-something Daniel and Emma, a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl, which stops short of becoming sexual and is handled with great sensitivity and insight. There follows for Daniel a move to a different city, an upturn in his fortunes, and a potentially happy marriage which fairly quickly turns sour. Realising that he has chosen the wrong life partner he sets out to find his now grown-up Emma once again.

The story’s theme is the gap between what we ask from life and what we actually get, which is presented as a mighty gaping chasm that can never be bridged. I found it uncomfortably realistic. A sobering read.

SEND ME AN EMAIL

|