|

"...And I Don't Even Like Science Fiction" |

|

Science fiction has a

serious image problem, and has

had for a long time. It isn't that

people don't like it, sci-fi films like

Star Wars and Jurassic Park have

been among the highest grossing

of all time, but a lot of people see it

as "non-adult" and essentially trivial

and refuse to take it seriously. I

must declare an interest, I wrote a

novel about artificial intelligence

called SIRAT that came out in the

year 2000, and the heading to one

of the first reviews it received on

Amazon was "... And I don't even

like science fiction". The gist of the

piece was that this woman had

read the book, presumably

unaware of its genre, and liked it in

spite of her anti-sci-fi leanings. All

credit to her for rising above her

prejudice, but this is a pretty big

barrier for a writer to overcome.

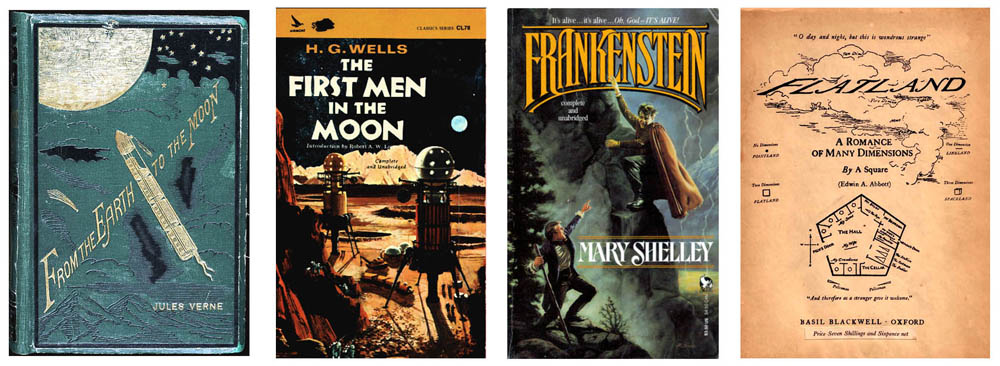

Historical Dimension

Science fiction has an honourable

pedigree, which some writers have

tried to push back to Classical

times (e.g. the flight of Icarus), but

the label only became attached to

the genre in late Victorian times,

when people began to get excited

about what science and technology

might be able to achieve. The

Victorians reasoned thus: We have

trains that can carry us around at

ten times the speed of a horse,

ships that need no sails, balloons

that can carry us thousands of feet

into the air. Where might it all

end? Could we have a vehicle that

would carry us to the moon (Jules

Verne From the Earth to the Moon)

or a machine that would allow us

to travel backwards and forwards

in time (H.G. Wells The Time

Machine), or might we even be

able to create an artificial human

being (Mary Shelley

Frankenstein)? Might there not be

intelligent beings on other planets

whose science is far superior to

ours (H.G. Wells The War of the

Worlds)?

As the achievements of science

became ever more spectacular

so did the speculations of science

fiction writers. Everyone

could see how radically such technologies

as electricity, radio, heavier-

than-air flight, the internal combustion

engine and scientific medicine

had transformed human life

and human society. It was but a

small step to imagine the social

changes that the next scientific

revolution might engender. What if

a technology came along that

allowed us to live forever, or to spy

on one another with hidden cameras,

or set up colonies on other

planets, or control people's

thoughts, or create artificial

brains? The speculations of the

science fiction writers expanded

with the ambitions of science itself.

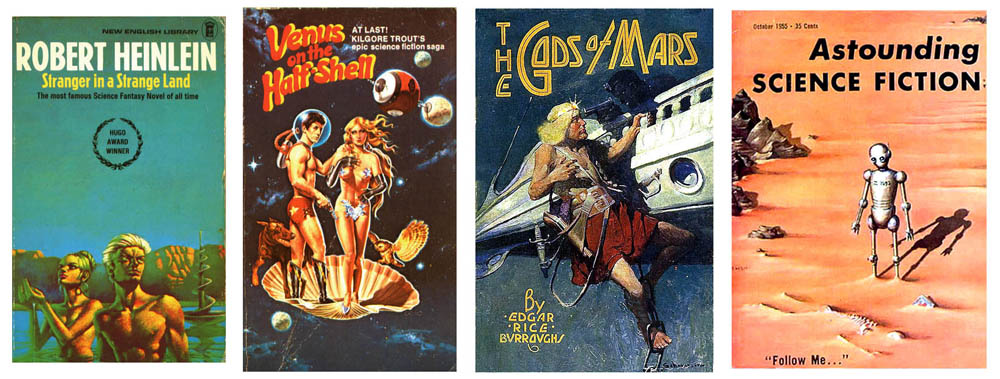

Space Fiction

I suppose a lot of people believe

that science fiction means space

ships, ray guns and meetings with

monsters on alien planets. The

cinema feeds this perception, with

films like the Star Wars series, the

Alien series, Starship Troopers,

War of the Worlds and the embarrassingly

similar Independence

Day; TV feeds it even more, with

such offerings as Star Trek, Dr

Who, Planet of the Apes, Lost in

Space, Blake's Seven, Battlestar

Galactica and many similar series.

Often there is cross-over between

the two, so that the Star Trek TV

series spawns the Star Trek feature

films, and the 1970s Planet of

the Apes feature films spawn successive

waves of Planet of the

Apes TV serials, leading in turn to

yet more Planet of the Apes feature

films. In reality all this is very,

very old-fashioned science fiction.

War of the Worlds was written in

1898 (!) and Star Wars is based on

the Flash Gordon and Buck

Rogers comic strips, first published

in the years between the

wars and continuing through World

War Two. It is, to a large extent, a

series of WW2 fighter-plane dogfights

transposed into a special

effects "space" setting. The golden

era of space fiction was between

the end of WW2 and about 1965,

when Charles Chilton wrote the

Journey into Space radio series

and Nigel Kneale the Quatermass

TV series. In the book world, Isaac

Asimov was writing his Galactic

Empire series, E.E. (Doc) Smith

his Lensman series, Robert

Heinlein his early space operas

like Starship Troopers (1959

source for the 1998 Paul

Verhoeven film!) and the Space

Cadet Ballantine series, and

Scientology founder L. Ron

Hubbard such rightfully forgotten

works as Forbidden Voyage, The

Emperor of the Universe and The

Conquest of Space.

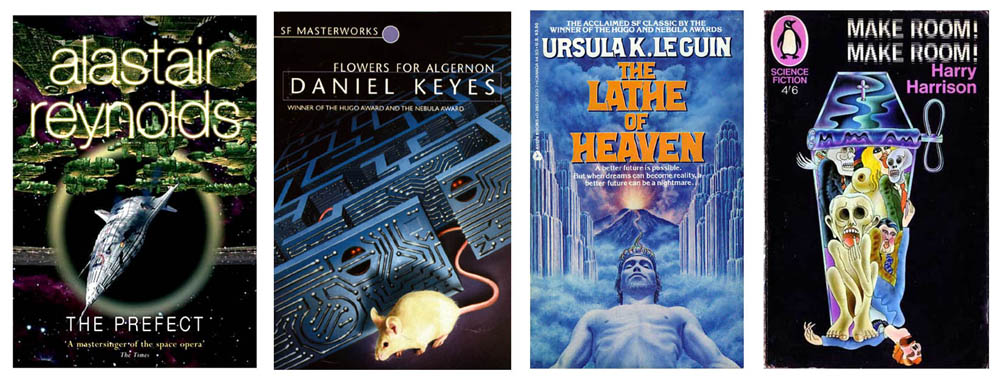

Retro Space Fiction

Yet there were, and are, people

still doing it: most notably Larry

Niven with his Ringworld series

(lampooned by Terry Pratchett in

his Discworld series) and Alastair

Reynolds, a Welsh physicist of

barely thirty summers, whose latest

offering The Prefect (May

2007) even sports a spaceship-adorned

cover that seems to harp

back to the days when the adventures

of Dan Dare were on Radio

Luxembourg and the latest edition

of Astounding Science Fiction had

just dropped through the letterbox.

Why would anybody want to write

this kind of thing in the 21st century?

Why would anybody want to

read it?

Other Kinds of Science Fiction

So where did science fiction itself

go? The answer is, all over the

place. The same authors like

Asimov and Heinlein, Arthur C

Clarke and Clifford Simak, who

had tried their hand at the ray gun

stuff in the Dan Dare years, started

speculating about immortality, free

will, telepathy, multi-world-line universes,

adjacent dimensions, different

kinds of reality, intelligent

robots, environmental catastrophe,

afterlife through the freezing of

dead bodies, races of genetically-engineered

super-humans and

human/machine hybrids. They

also introduced into their writing

philosophical speculations up to

and including the nature of the

Universe and of various imagined

versions of its Creator. Post-nuclear

wastelands and other

dystopias here on earth replaced

the acid seas and man-eating

fungi on distant planets. Each new

technology, such as the computer,

genetic engineering or virtual reality,

was pushed to its logical conclusion

and a bit beyond to see

where it might possibly take us if

we let it run forward unchecked.

Social issues like attitudes to

women (The Stepford Wives),

over-population (Make Room!

Make Room! and its screen adaptation

Soylent Green) and the possibility

that artificial intelligence

might supersede our own

(Asimov's Multivac stories, the

Terminator series, HAL in 2001,

Supertoys Last All Summer Long

and its screen adaptation AI, and

my own humble SIRAT) were all

explored. But still the stigma of the

Dan Dare years persisted, and a

convention was adopted that any

work that was good in the literary

sense would no longer be called

science fiction (1984, Brave New

World, Flowers for Algernon,

Metamorphosis, Naked Lunch,

Solaris, The Midwich Cuckoos,

Slaughterhouse Five).

Cyber Punk

In the 1980s and 90s a new sub-genre

emerged, written mainly by

the computer-game generation

and usually set in a future dystopia

in which computers and people

had reached some new level of

integration. It was usually peopled

by the violent and alienated young

who swore a lot, took drugs which

might totally change their view of

reality, filled their lives with loud

music and communicated with one

another in an invented slang of

their own. This was cyber-punk.

Anthony Burgess anticipated most

of its elements in his 1961 A

Clockwork Orange, but it had to

wait for the IT revolution and the

Internet to attain its full potential. A

recent mainstream spill-over from

this genre was the Matrix series of

films, within which space was

found for a bit of Kung Fu and a

few lively car chases for good

measure, and the similar but significantly

different Equilibrium.

Can We Sum It All Up?

With the proliferation of sub-genres

and the emergence of more

experimental kinds of writing it is

no longer at all clear what is and

isn't science fiction, whether in

books or on film. Perhaps it doesn't

matter, but if the term is to be

used as a way of dismissing work

as valueless without examining it,

then it matters at least to writers.

The Very Best Kind

Science fiction, in my opinion, is at

its best when it reveals a way of

seeing things that I was never

aware of before. I could say precisely

the same of the formal study

of philosophy, and, at least for me,

the difference between the two is

mainly one of presentation. An outstanding

example of science fiction

as philosophical exploration

would be Stanislaw Lem's Solaris,

in which the inhabitants of a space

station investigating the seemingly

sentient ocean that covers an alien

planet come under reciprocal

investigation themselves from the

planetary-sized organism. The

ocean tries, in a faltering but

benign way, to give them what they

want. The question at the heart of

the story is: Can human beings

ever be given what they want?

What is the fundamental aim and

fulfillment of human existence?

Tarkovsky's 1972 film is about a

tenth as good as the book itself,

Stephen Soderberg's 2002 adaptation

about a fiftieth as good, but

that makes both of them excellent

films. |